General Overview

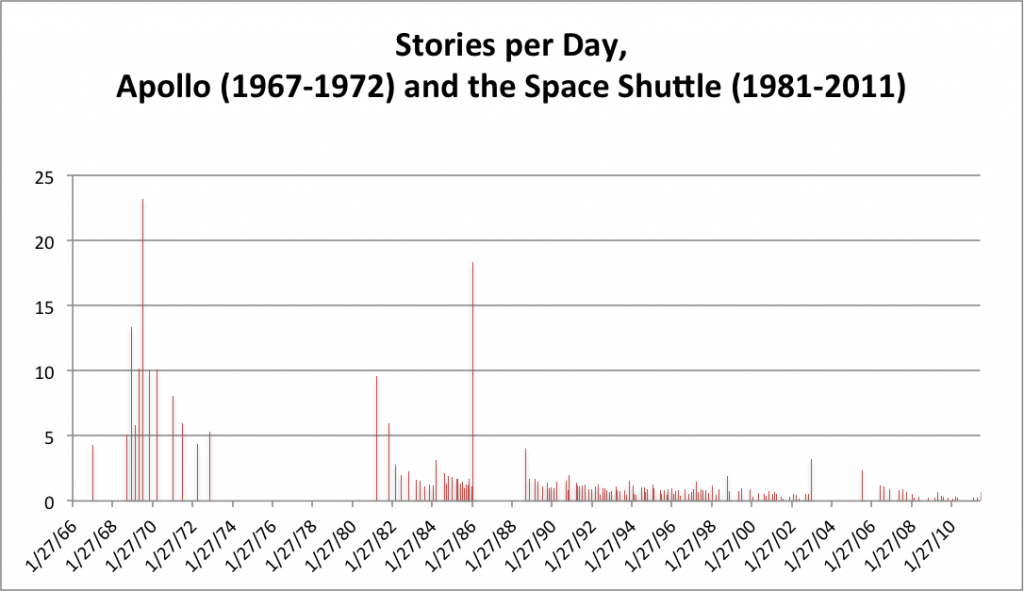

Chart 1.1 – Stories per Day, Apollo (1967-1972) and the Space Shuttle (1981-2011)

The easiest observation one can make about the data is purely quantitative and relates to the amount of stories published for each mission. Because all 147 missions varied in length from 1 minute and 13 seconds (Challenger disaster, STS-51L) to over 17 days (Columbia, STS-80), merely charting the total number of stories published isn’t the best way to determine frequency of publication. Instead, Chart 1.1 plots the number of stories published per day analyzed.

In general, Chart 1.1 illustrates the declining appeal of space-related stories to New York Times readers. Spikes in coverage are evident for “new” missions, such as Apollo 11’s moon shot or STS-1, the first flight of the shuttle. Additionally, coverage spikes for disasters and the flights directly following them.

For example, coverage increased in the wake of Apollo 1, the Challenger disaster, and the Columbia disaster. Interestingly, coverage remained relatively stable after Apollo 13, but this could be because it was the only “disaster” that did not see the loss of human life. Additionally, the nation might have still been “high” on moon-related coverage so a spike may not have been as likely.

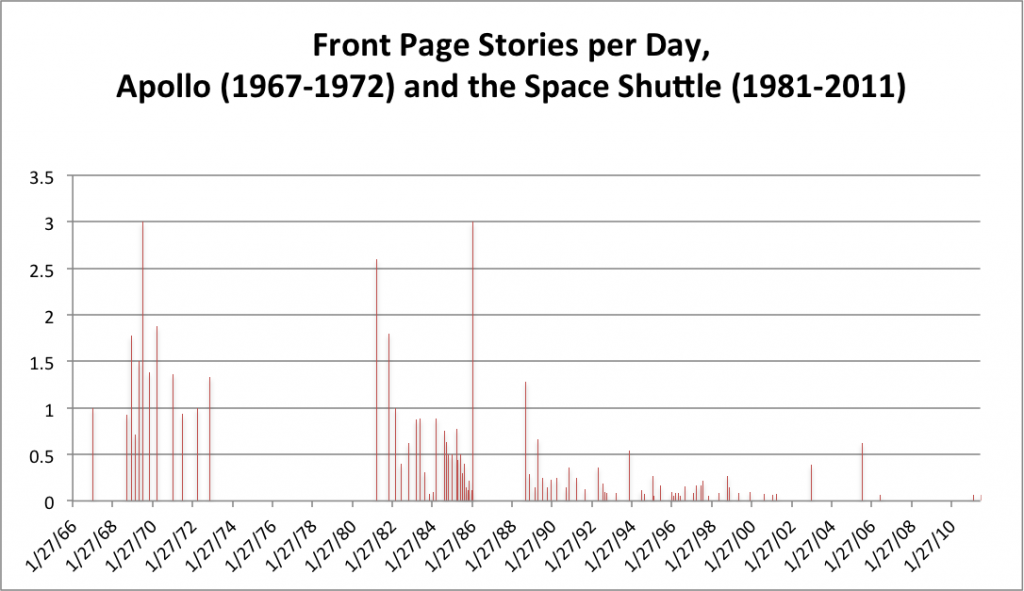

In addition to the total number of stories per day, the total number of front-page stories in this sample is significant. Chart 1.2 illustrates the amount of front-page stories per day of each mission examined.

Chart 1.2: Front Page Stories per Day, Apollo (1967-1972) and the Space Shuttle (1981-2011)

Like Chart 1.1, Chart 1.2 illustrates the waning interest of the news consuming public, especially in the years following the Challenger disaster in 1986. This front-page analysis suggests three distinct periods of space coverage: an Apollo period, an experimental Space Shuttle period, and a routine Space Shuttle period.

The Apollo period appears to have generated much interest that peaked, unsurprisingly, at Apollo 11. Still, only a handful of Apollo missions saw fewer than one front page story per mission day. Contrast this with the Space Shuttle’s tenure, which had only 5 missions out of 135 with at least one front-page story per day, and the contrast becomes clear. In fact, 117 of the 135 Shuttle missions didn’t even see a front-page story every other day.

In the new millennium, 31 of the 39 Space Shuttle missions were not granted one front-page story during the entirety of flight. Notable exceptions to this trend were the space Shuttle Columbia’s disastrous descent and the mission directly following it.

None of these findings should be a surprise to even a novice follower of U.S. top stories. Indeed, more analysis is necessary to determine whether there has been a noticeable content shift in headlines. While the amount and placement of coverage in the Times relevant to the question of shifting journalistic attitudes toward space, we must go deeper.

(Note that you can click any chart listed here to see a high resolution version.)

Inclusion of Names

Chart 2.1: Mention of Names, Apollo (1967-1972) and the Space Shuttle (1981-2011)

The first variable coded in this research pertained to the inclusion of names – first, last or otherwise – of either astronauts on missions or tangential story characters. These tangential characters are astronauts’ wives, political figures commenting on missions and programs, foreign leaders, or NASA employees.

Naturally, headlines that refer specifically to astronauts connote a sense of personal grandeur for the men and women in space. In the days of Apollo, stories were more likely to make reference to astronauts by name, while in the later days of the Space Shuttle program stories were more likely to refer to a “crew” composed of nameless astronauts and scientists.

Chart 2.1 illustrates the decline of personal mentions over time. While this could be a journalistic phenomenon related to space saving and shifting headline conventions, it is more likely that Americans simply grew weary of remembering crew names on 135 Shuttle flights that took place mere months apart.

An interesting exception to the trend of nameless headlines occurred in 1998, when congressman and astronaut John Glenn joined the crew of STS-95 at the ripe age of 77.

Reference to Specific Missions & Crafts

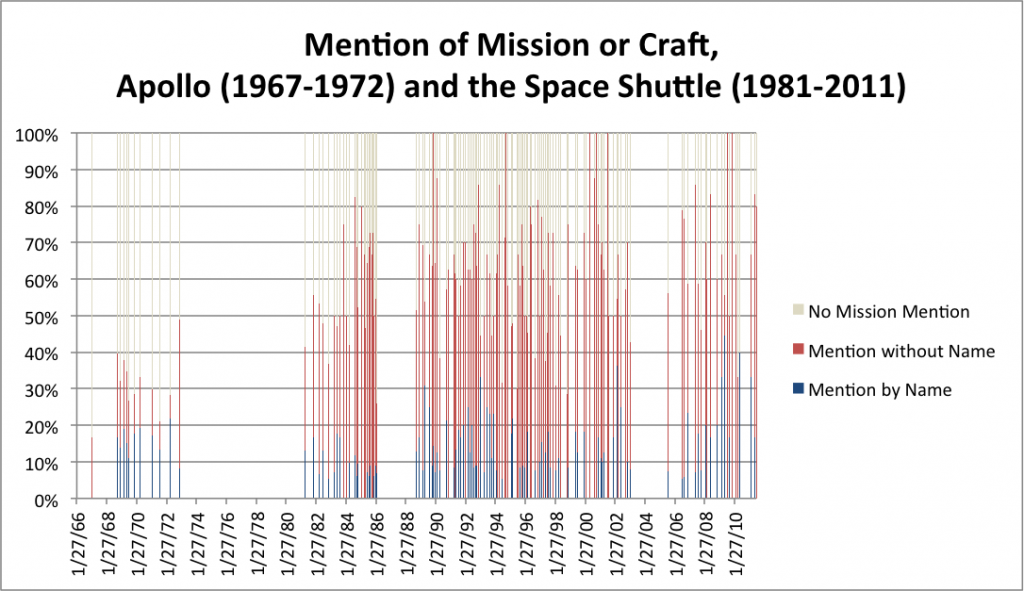

Chart 3.1: Mention of Mission or Craft, Apollo (1967-1972) and the Space Shuttle (1981-2011)

Just as Chart 2.1 referenced the instances of specific mention of human names, Chart 3.1 illustrates instances where headlines made specific reference to missions or spacecraft.

During most missions, reference to missions (such as Apollo 12) or spacecraft (such as Discovery or Atlantis) constituted the smallest percentage of total headlines. The remaining possibilities – reference to a general program (“Apollo” or “Space Shuttle”) and no reference at all – constituted the remainder of the headlines analyzed.

While the frequency of references to missions or crafts by name tended to be variable, the frequency of references to missions or crafts in a general sense grew over time.

Why is this? It could be because of the news consuming public’s familiarity with spaceflight or its inability to recall specific crafts. It could also be a matter of headline-writing convention. However, a more likely suggestion is that because there were so many Space Shuttle missions, reference to “the shuttle” became commonplace. After all, a fleet of (similar-looking) spacecraft that perform essentially the same functions is likely to represent one monolithic entity in the minds of an otherwise unquestioning public.

In the days of the Apollo program, flights were fewer and more varied in purpose. It is conceivable, then, that specific reference to the names of Apollo flights was necessary. Additionally, the unknown aspects of lunar travel, coupled with the Cold War, might have caused people to think of each mission as a rallying event.

Humanizing Astronauts vs. Championing Mission Achievements

Chart 4.1: Mission Pride and Humanization, Apollo (1967-1972) and the Space Shuttle (1981-2011)

Unlike the mention of human and mission names represented by Charts 2.1 and 3.1, Chart 4.1 fails to suggest many overarching trends. For every mission of both the Apollo and Space Shuttle programs, headlines that “humanized” astronauts or suggested pride in the result of a particular mission formed the clear minority.

The idea behind coding for “humanization” is simple: stories that portray astronauts as ordinary people are less prone to present astronauts as routine workers. Headlines regarding astronauts’ wives, home lives, upbringing, faith, sense of humor, and childlike appreciation of weightlessness all serve to “humanize” astronauts.

Similarly, headlines that focus on a mission’s successes, sensationalism, or ability to inspire awe serve to portray individual missions as something other than routine.

As Chart 4.1 illustrates, the tendency of articles to focus on the non-routine is variable and not indicative of an overall difference between the Apollo and Space Shuttle missions.

Scheduling Future Events

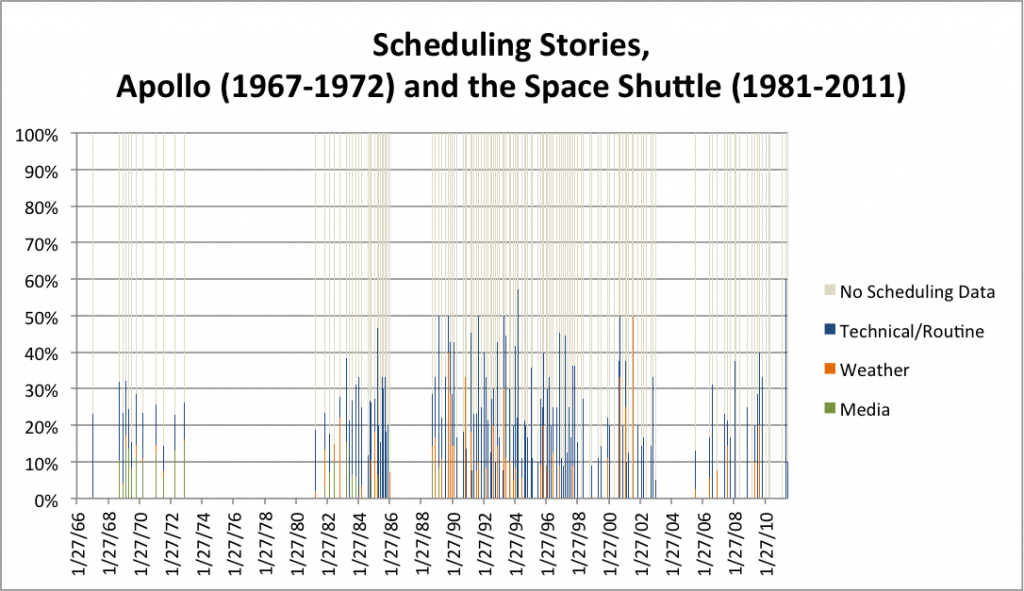

Chart 5.1: Scheduling Stories, Apollo (1967-1972) and the Space Shuttle (1981-2011)

If, as Chart 3.1 suggests, readers became “used to” the mention of space flight, it follows that missions might have been becoming routine. Part of this analysis measured whether headlines indicated a future, or scheduled event. The thinking behind this measurement is that as a news story becomes more routine over repeated occurrences, the public is less curious about events, like a space walk, that are going to happen in the future.

Chart 5.1 illustrates the frequency with which such references to future scheduled events occurred in the headline sample.

The most obvious shift in scheduling stories occurred throughout the Apollo missions and at the beginning of the Space Shuttle missions, when media schedules were regularly included in the Times so people could plan to watch launches, landings, and press conferences at home. By the mid-1980s, however, these scheduling pieces were no more.

Additionally, mentions of delays or schedule alterations caused by inclement weather – whether at a launching site, landing site, or otherwise – increased following the ice-related Challenger disaster in 1986.

Finally, notice the prevalence of stories without any sort of scheduling aspect. In a vast majority of the missions analyzed, headlines lacked any sort of indication of what would happen in the future. While this is generally the case for all the missions, the Space Shuttle mission headlines tended to incorporate more of this “null” category than the Apollo mission headlines.

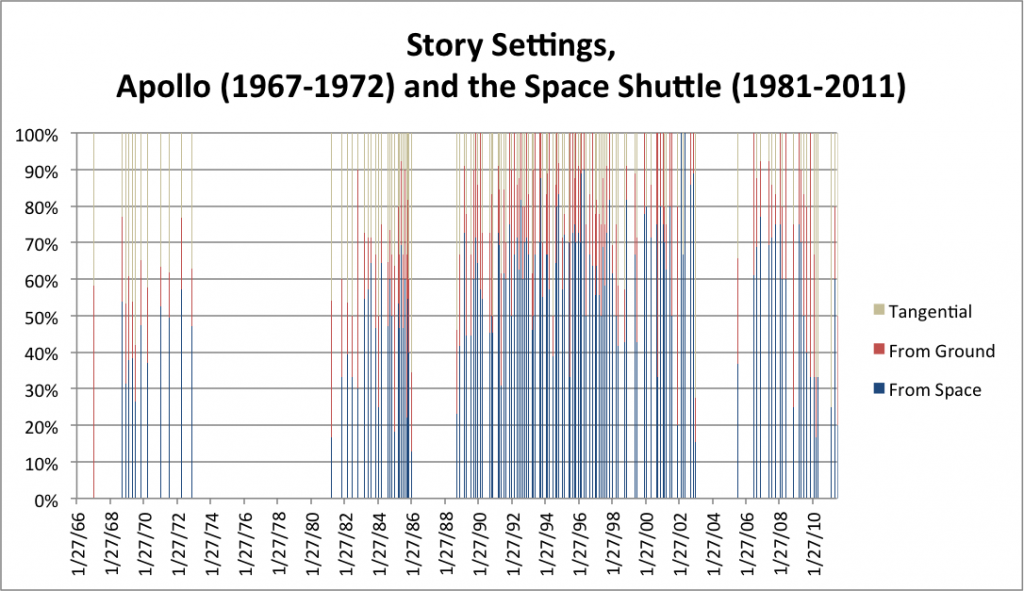

Story Setting

Chart 6.1: Story Settings, Apollo (1967-1972) and the Space Shuttle (1981-2011)

We’ve looked at specific references to names and missions, the tendency of headlines to champion missions and the people on them, and the inclusion of future plans in headlines to determine whether the routine nature of more recent space travel has been detrimental to news coverage. But where do these headlines come from? That is, what are the stories about?

By coding for headlines based in space (those that make specific reference to activities occurring onboard spacecraft), on the ground (those that make specific reference to activities related to launch sites, landing sites, or NASA mission control), or around the world (other, tangential stories), we can infer which missions were perceived as routine or novel. Chart 6.1 illustrates the changing percentages of each of these story settings.

Generally, “routine” missions are comprised of space- and ground-related stories. Tangential stories, like hometowns celebrating their astronaut residents or decrees from the president, tend to be associated with missions that lack a sense of normalcy.

That’s why we see more tangential stories in the days of Apollo, as well as the beginning and end of the Space Shuttle program. Space disasters also tend to produce a spike in tangential stories.

The most telling aspect of Chart 6.1 is the increasing amount of space-centered headlines and the decreasing amount of tangential stories. This would suggest a readership that did not appreciate the technological marvel of the space program, since the headlines written to attract customers’ eyes will be tailored to what sells.

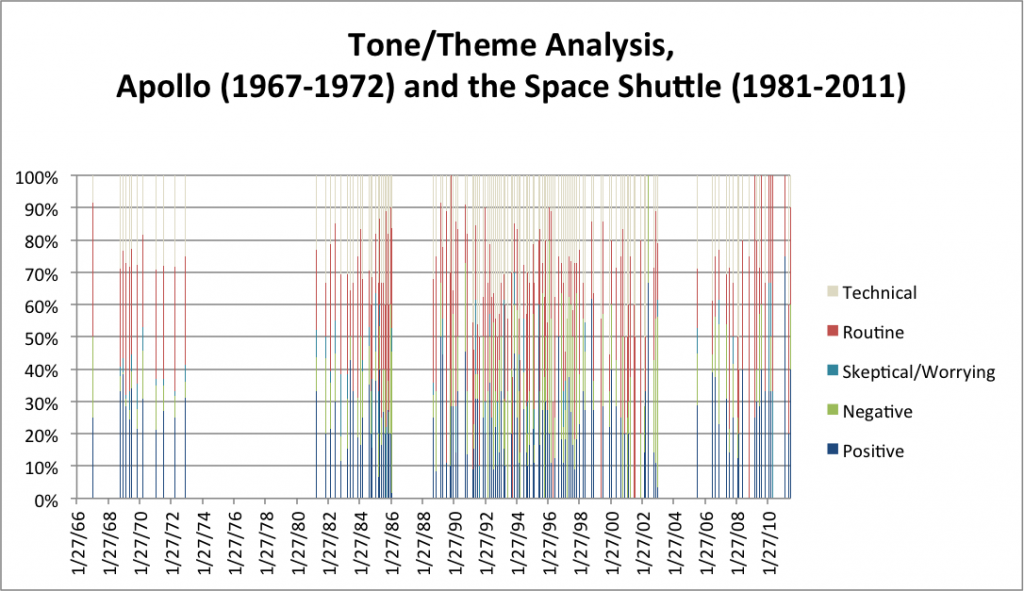

Tonal/Thematic Analysis

Chart 7.1: Tone/Theme Analysis, Apollo (1967-1972) and the Space Shuttle (1981-2011)

Finally, each of the 2,801 headlines gathered was coded according to a system that described it as either positive, negative, skeptical, routine, or technical. This analysis can reveal general trends in headline composition. Chart 7.1 illustrates the changing nature of coverage over time, but let’s take a look at each variable individually.

Chart 7.2: Average Positive Stories, Apollo (1967-1972) and the Space Shuttle (1981-2011)

The average number of “positive” headlines per mission varied throughout the Apollo and Space Shuttle programs. Even during the heyday of the lunar missions, solely positive headlines made up less than 40 percent of all stories analyzed. That number increased, perhaps not surprisingly, to more than 70 percent during the final mission, as the Times’ correspondents and editorial staff became nostalgic about the finished program.

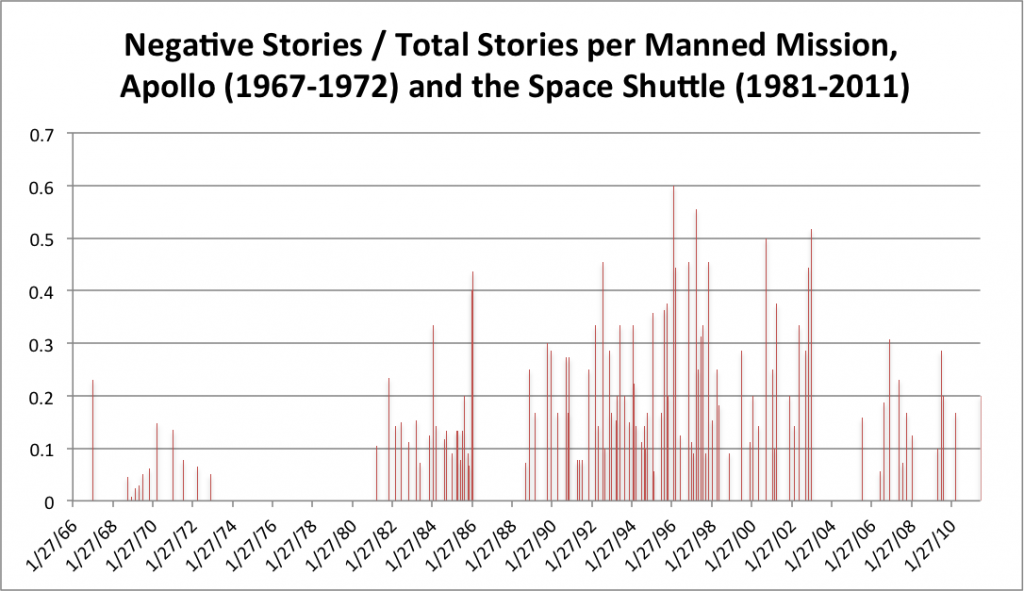

Chart 7.3: Average Negative Stories, Apollo (1967-1972) and the Space Shuttle (1981-2011)

Although the average number of positive headlines varied, a trend can be seen in Chart 7.3, which illustrates the degree of negative representation in headlines as it grows steadily over periods of time. Of course, negative headlines tend to spike around disasters, and Chart 7.3 affirms this notion.

Also, the disparity between the degree of negative headline representation of Apollo and the Space Shuttle program is clear. Aside from the doomed Apollo 1, nearly all of the Apollo missions tend to have a lower percentage of negative stories than the Space Shuttle missions.

In fact, the average number of negative stories for the shuttle missions rises until about the mid-1990s. Some possible explanation for this trend are the assistance the Space Shuttle was forced to give a hobbled Mir in the late-1990s or the problems the shuttle had with the Hubble Telescope during that decade.

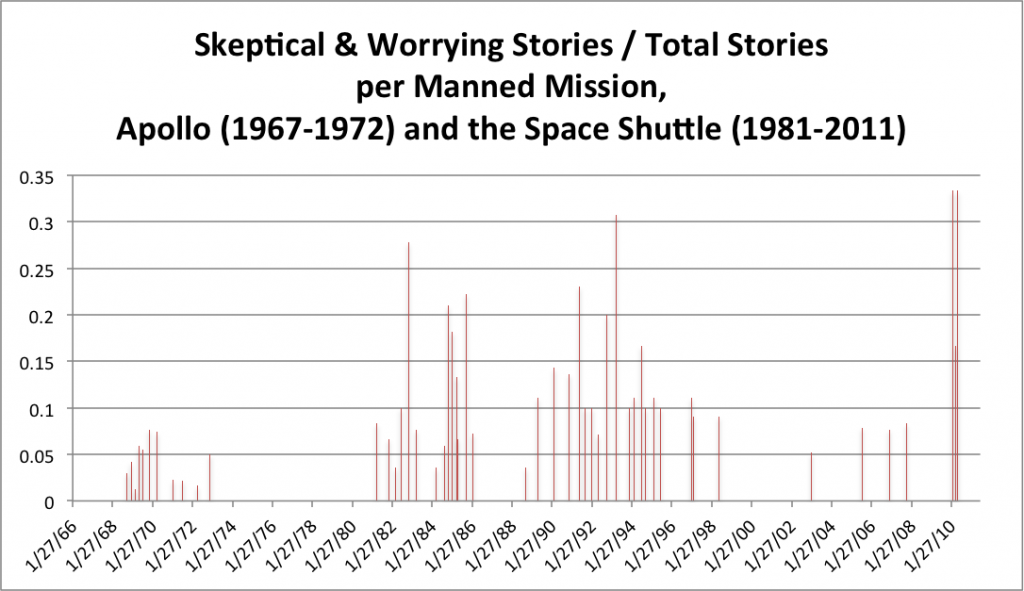

Chart 7.4: Average Skeptical/Worrying Stories, Apollo (1967-1972) and the Space Shuttle (1981-2011)

Just as negative headlines became more commonplace after Apollo, so too did headlines with connotations of skepticism or worry. As Chart 7.4 illustrates, however, this skepticism was not found as frequently as negativity as the Space Shuttle program continued. (In fact, of the 135 shuttle missions, only 40 were reported on with a hint of worry or skepticism).

Most of the skepticism that did rear its ugly head during the Apollo and Space Shuttle missions was concerned with the astronomical economic commitment required to go to space. Indeed, the period with the most frequent headlines tinged with skepticism and worry was the first years of the Space Shuttle. Initially, skeptics questioned the fiscal commitment. After Challenger, they questioned the danger versus payoff. And worry ran rampant during the first years of Hubble’s (lack of) operation.

Still, skepticism and worry waned in the new millennium, despite the breakup of Columbia in 2003. This might suggest, as has been suggested before, that we became complacent with the routineness of government-sponsored spaceflight.

Chart 7.5: Average Routine/Repeating Stories, Apollo (1967-1972) and the Space Shuttle (1981-2011)

If we began to take spaceflight for granted during the Space Shuttle era, it is conceivable that “routine” stories became commonplace during that time. As Chart 7.5 illustrates, that might be the case, if not for the variability in the degree of routineness in the headlines examined.

Chart 7.5 presents “routine” headlines, or those headlines that repeat themselves from mission to mission: uneventful launches and landings, profiles of astronauts on each mission, and routine tasks that are reported on in passing.

The average amount of “routine” stories stay relatively constant during the Apollo missions, but began to fluctuate as the Space Shuttle undertook new tasks, such as chasing satellites, helping Mir, constructing the International Space Station, and so on. When the shuttle first undertook these tasks, the headlines were anything but “routine.” After successful, novel missions, however, the number of routine headlines grew again.

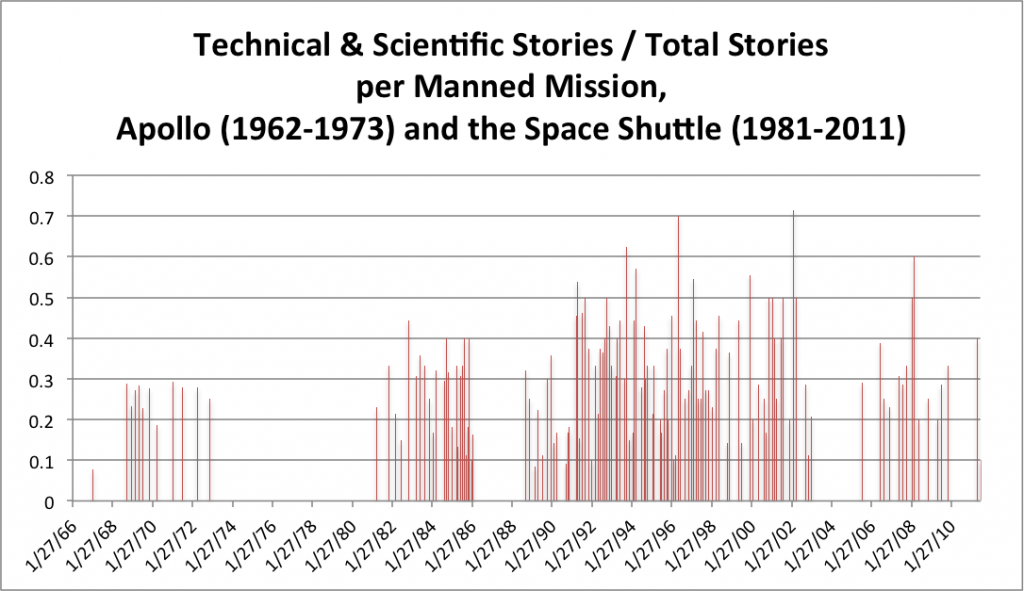

Chart 7.6: Average Technical/Scientific Stories, Apollo (1967-1972) and the Space Shuttle (1981-2011)

Chart 7.6 illustrates the tendency of headlines to include technical or scientific language specific to a particular mission. It shouldn’t be surprising that as time goes on, more of these headlines occur.

After all, the public in the new millennium likely has a better grasp on the intricacies of orbits, docking, rocketry, and the like than Americans during the Apollo years. As time progressed during the last half of the twentieth century so, too, did the technological acumen of the New York Times’ readership.

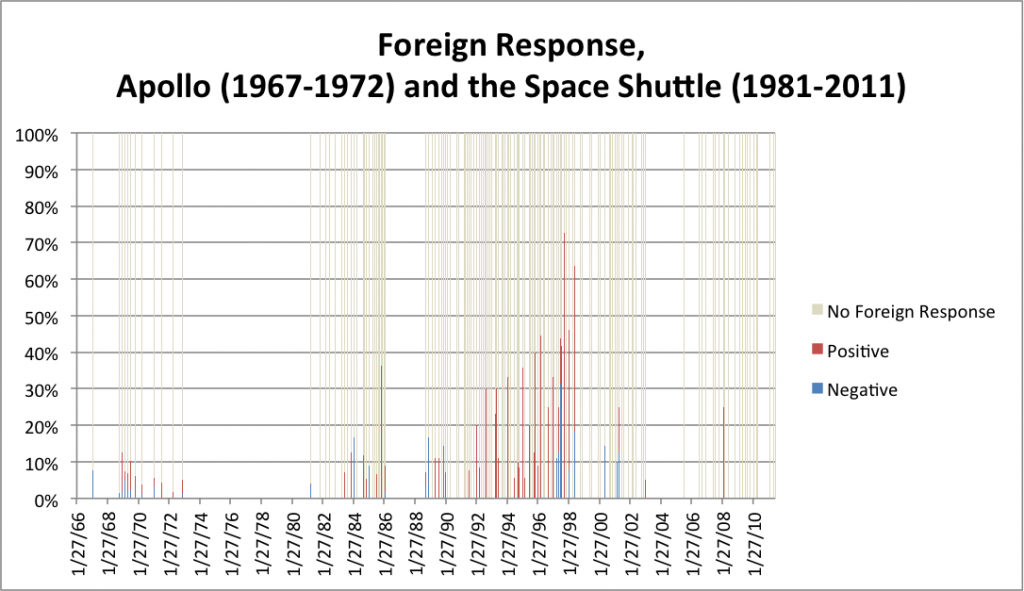

Foreign Reaction

Chart 8.1: Foreign Response, Apollo (1967-1972) and the Space Shuttle (1981-2011)

It’s no secret that the impetus for John F. Kennedy’s support of lunar exploration came from Moscow. The Soviets beat the U.S. into orbit, forcing them to join the space race.

That’s why foreign response is an essential variable in this content analysis. Granted, not all references to international opinion can be made in the tiny headline area, but references to foreign powers were used in some headlines.

As Chart 8.1 shows, however, the inclusion of foreign response – positive or negative – was not a standard practice of the New York Times. And while you might expect to see lots of negatively framed foreign stories during the Cold War, positive stories generally outnumber these. These positively framed headlines involving foreign leaders and countries tended to be notes of congratulations or celebrations of mission achievements abroad. Still, there is not enough data to justify any conclusions from Chart 8.1 alone.

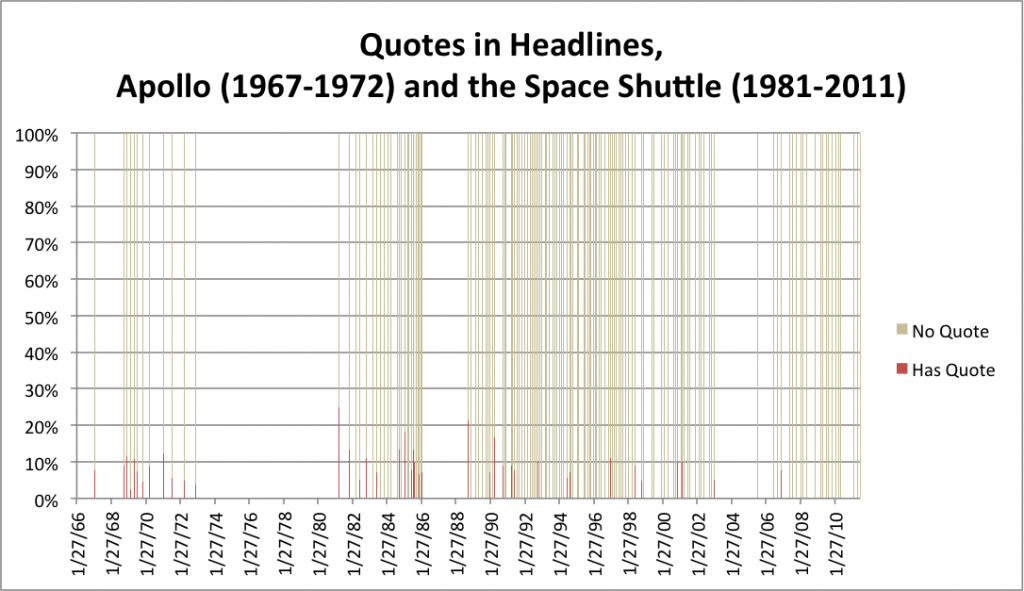

Use of Quote

Chart 9.1: Quotes in Headlines, Apollo (1967-1972) and the Space Shuttle (1981-2011)

The final variable sought via headline coding was the existence of a quote. Headlines with quotes from astronauts serve to humanize those space travelers, and quotes of tangential figures on earth mark “non-routine” missions. Every Apollo mission included a quote, while very few Space Shuttle missions did. Those shuttle missions that did incorporate quotes tended to occur earlier in the program.

While the lack of quotations in headlines about the Space Shuttle program might suggest that stories came to be less personal and more routine, it is actually more likely that the style of headline writing evolved at the New York Times: early headlines were long, had multiple parts, and covered more than only one topic. Printers placed “blocks” of text on a manual press for which long, descriptive headlines were appropriate. With the advent of digital publishing in later years, however, headlines did not need to be so structured.